Written by Molly Kampf

Copyright 2018

Breath is happening. Without conscious thought,

our body naturally regulates and performs this activity.

So what is breathing?

Breathing is an involuntary activity that provides our bodies with fresh oxygen and rids us of carbon dioxide. We sleep, talk, eat and go up and down stairs while our bodies coordinate the incoming and outgoing air. Without thinking about breathing and we are able to thrive on its outcome. There is also some conscious control over this involuntary action of our body. Therefore, at some point we do think about breath – we take a deep breath to focus, we guide it during exercise, while we are singing or just because. The way we think about how we breathe can affect it; and the tendency is to take over and improve what is already happening. F.M. Alexander said this; “If I breathe as I understand breathing, I am doing something wrong.”¹ Meaning we can interfere negatively if the assumed directions are contradictory to organic breathing. This article will clear up some possible misconceptions about breathing and detail parts that are often reduced to a quick easy phrase that fails to explain what is actually happening during respiration.

A student I will call Becky asked me once why she needed to know about breath. As a dancer and undergraduate student, Becky spent a lot of time moving, studying at a desk or sofa, carrying heavy books, rushing and stressing about her workload. I noticed that she held her breath when she was talking, picking up her bag and thinking. When she was tired or talking about stressful topics, she would hold her breath and let it out quickly after she spoke. There were two reasons to address breath early in our Alexander Technique lessons together. First, breathing had no space in Becky’s stressful life. Second, her constricted breath was a holding pattern that included other parts of her body- her arms, ribs, neck and head. For Becky to free herself from this holding pattern in other areas of her life she had to first regain the movement that organically happens when breathing.

As an Alexander Technique teacher, I don’t tell you what you are doing wrong, I help you to become more aware of your body and movement so that you can find what works and what doesn’t, and understand why. I educate using directions and physical relationships in your structure, as well as my hands* to guide your alignment or help you notice a specific occurrence. Along with the hands-on part of Alexander Technique, in my practice I use anatomy-based image, video, description and a technique called body mapping. Body mapping, as developed by Barbara and William Conable, is a way of learning anatomy and specifically applying the teachings to your own body, movement, and in this case, breathing. Often when people look at the size of the lungs for the first time, they are surprised at how large they are, and that part of the lungs are in their armpit region and just below their collarbone. Some of the anatomy-based education taught in a particular lesson may include: bones (their shape and size), joints (hinge, ball and socket, pivot, gliding- each move differently), muscles (the way the fibers stretch and where they connect), organs, and systems (nervous, respiratory, circular, etc.). As you clarify the physical map in your mind and bring awareness to the sensation of that area, subtle movement becomes noticeable and large movement becomes easier.

A memorable lesson with Becky started with her sitting in a chair. As she sat there I talked about the stability of the ground and the hard chair with a back that was supporting her. Next, I brought her attention to her ribs against the back of the chair and for her to feel how they moved up during her inhalation, back down during her exhalation. Becky was surprised how easy it was to ignore this sensation even through it happened frequently. The lesson continued with using my hands to gently guide her awareness to the ribs in back and at the side, as well as her neck and head. While I worked with her using my hands, I continued to describe the movement happening during breathing. At the end of the lesson, I had her put on her backpack and feel these same occurrences.

Throughout my practice I have observed a number of common misconceptions and questions that frequently arise when teaching breathing. Here are a few topics that surfaced during my lessons with Becky that demonstrate myths I frequently encounter:

- Breathing begins at our nose or mouth when air enters our body.

- Breathing from the belly creates a full breath.

- Our chests rising and lowering is what moves air in and out of our body.

- The inhale and exhale should be the same length.

I will further discuss each of these myths below for you to gain a more detailed outlook on breathing.

Myth #1: Breathing begins at our nose or mouth when air enters our body.

From the outside eye, it appears that breathing begins when air comes through our nose or mouth. Actually, the act of breathing begins before this, and air moving in through our nose or mouth is the result. Let’s go through a breath from the very beginning. First, there is a call from the body to the brain for action, and a response from the brain to begin. Increases in carbon dioxide levels in the blood stream signal the part of the brainstem called the medulla oblongata to increase the respiratory rate and begin the inhalation. Next, is the first visible movement: the contraction of the diaphragm, quickly followed by the contraction of the external intercostal muscles and scalene muscles. It is through the major work of the diaphragm that the rest of the body responds and achieves the inhalation. The diaphragm moves our organs down and away to make space for the lungs to expand and receive oxygen. In the other direction, the external intercostal (between ribs) and scalene muscles (part of neck) increase the dimension of the rib cage by lifting and widening the ribs. In the space created by muscles moving in opposite directions, alveoli; the tiny air sacs at the edges of the bronchioles enlarge, generating a pressure change in our lungs. Air flows from places of high pressure to lower pressure. As the pressure changes in our lungs becoming lower than the atmosphere outside of our body, air enters through the nostrils or throat; then flows down through the larynx, trachea branching into the left and right bronchus, branching more into many bronchioles and into the alveoli. This air enters because of this pressure change, not the action of sucking air in via musculature use. In the alveoli, oxygen exchanges with carbon dioxide. Once they have switched places, exhalation begins; the oxygen diffuses into our blood stream and the carbon dioxide travels up the same pathway and out through the nostrils or mouth²·³. (See #2 for more details about exhalation.)

On average a healthy adult at rest breathes 12-20 times per minute and sighs every 5th or 6th exhale. Yet, there are extremely precise conditions within our body that the breath regulates. This all is part of healthy functioning lungs. The variance allows for alveoli and cell function as necessary to serve greater responsibilities- health and pH balance within the body through the respiratory and circulatory system²·³. I am not telling you this to have you start counting and changing patterns to be sure you are in this zone. I’m telling you this so you can marvel at what an incredible range there is! Even at rest, you could breathe almost twice as many times and stay within an acceptable range.

It is difficult to feel the diaphragm work, and because it is a powerful and automatic muscle, it is best left to its own task without interference anyway. The diaphragm is responsible for about ¾ of the muscle action of inhalation, with the external intercostal and scalene muscles performing the other ¼ work. It is easier to feel the result of the action of our diaphragm- our organs shifting, as well as the result of changes of pressure in our lungs- air moving into our nose and mouth. Nonetheless, the action of inhalation can be best described as beginning at the diaphragm. You can take your mind off breathing and know that you are alive and functioning; with blood oxygenating and carbon dioxide leaving the blood stream, all thanks to your diaphragm and your autonomic nervous system.

As I worked with Becky I introduced a few anatomical terms; muscle contraction (work) and how the muscle fibers tighten when this happens. We traced the bottom and top of her ribs, and counted ribs to find the bottom of the diaphragm as well as the shape of her lungs. I don’t expect students to memorize body parts, attachment locations or the specifics of the oxygen pathway. There is never an expectation of having prior knowledge or retaining specific anatomical terminology. I am more interested in students having a visualization combined with kinesthetic sensation. This is how Becky was then able to sense the rib movement within her own body while sitting in a chair.

Myth #2: Breathing from the belly is a full breath.

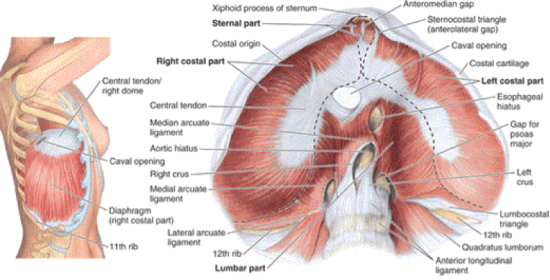

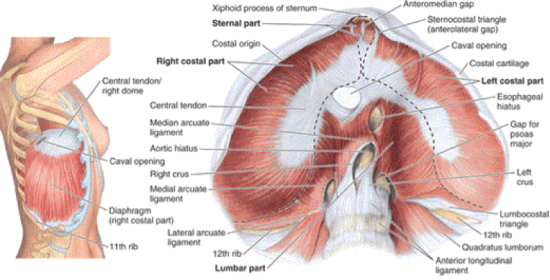

“Breathing from your belly” is a phrase often used that can create misconceptions about how much muscle is needed to breath as well as the exact location of various body parts. Movement in the belly is a result of your diaphragm’s descent making your digestive organs slide down and away. This powerful muscle is the separation between our thoracic cavity (heart and lungs) and the abdominal/pelvic cavity (digestive system and other organs). The diaphragm is located beneath the lungs and is shaped by the organs below that rise up beneath it. The diaphragm is a muscle with a strong central tendon. It is shaped much like a dome, ascending into the rib cage and down lower at the spine. It attaches to bone in the front at the xiphoid process (lower sternum), the inner surface of the lower six ribs, and the top three lumbar vertebrae. Its job is to move down and spring back up, always in constant relation to the organs surrounding it; both above and below. Look at the images below:

4

5

5

6

This dome lowers about 3-8 centimeters during inhalation and then retreats back up during exhalation. The variance of this measurement is due to size, health, age and breath. The diaphragm muscle is contracting (working) when it goes down and is relaxed as it goes back up. A full inhale includes feeling a slight pressure down and out that begins at the thoracic diaphragm and goes around your ribs to the spine. This down and outward pressure can be felt all the way down to the pelvic floor. This movement is slightly more forward than backward, as the floating ribs and pelvis curve toward the front of the body.

In exhalation, the movement of the diaphragm upward is guided by the organs returning to their rightful place in and up not working muscles. Inhale creates exhale; the abdominal organs buoyantly go back in and up to their resting position, without having to engage abdominal and core muscles. Elastic recoil is an automatic and passive rebound of the ribs lowering and organs returning to their nestled position in and upward. This automatic response occurs during exhalation; if you are quietly breathing, without force or need to assist, there is no muscle work.

As you read in Myth#1, the movement of the diaphragm is an involuntary reaction to the need for change in gases within our blood. Pushing your belly out and in with your abdominal and core muscles is a common misconception that you are breathing from your belly. The accessory muscles of exhalation are the abdominals and internal intercostal muscles. These are the working muscles if you are purposely forcing more air out with a deep exhalation, because of physical activity or health condition. These muscles are not working if you are quietly exhaling and not necessary for general breathing. We don’t need to force our breathing; we should allow it to happen.

As Becky learned to breathe without unnecessary work and gave a bit of attention to the moments when she was holding her breath, she was able to notice where she was within the breath. Then she could remind herself of what comes next. She continued the extent of her inhale by thinking about the actual pathway of air and how it enters and exits the body.

Myth #3: Our chests rising and lowering is what moves air in and out of our body.

As you have already read, there are several parts that move during a breath. Our diaphragm, lungs, spine, ribs, organs and digestive system are the main movers when breathing. Some movement is quite subtle- like the spine. Some is easier to recognize- like the lower organs. Yet, all of these movements happen as a part of breathing, are involuntary and we do not need to interfere to make them occur or happen better.

Try This:

Pay attention to your body and take a few breaths while thinking about “chest rising”. This is an action of lifting your rib cage and spine together up and down starting at your lumbar spine. It feels like your sternum and rib cage moving through space. The movement of breath is different from this action.

Spending time examining the shape of a bone will help to understand how it moves. Each rib is round and curves individually from the sternum in front to its rightful vertebra in back. Collectively the ribs create the rib cage, although they each move marginally separate. Their movement is like a bucket handle, rising and lowering slightly. Look at the image below:

7

You can feel movement of the ribs not only as “your chest rising” but also as your sides and back expanding and rising as you inhale.

Now, try taking a few breaths as you think about how your ribs consist of front, side and back. It is not just your chest moving, but a circular “up” that happens when you inhale. If you are only thinking about your chest rising there is a lot of available movement you are missing in your inhalation.

On an inhale the movement of the:

Diaphragm- lowers and flattens.

Organs- pushed down and spread outward by the diaphragm.

Lungs- go forward, backward, upward and downward.

Ribs- spread outward and upward, with the external intercostal and scalene muscles located between and above contracting, all the way from the back, around our sides to our sternum, making space for the incoming air.

Spine- gathers moderately within its natural curves. (This movement is almost undetectable and should never be accentuated.)4

Arms- go along for the ride, receiving the ribs movement underneath, although are not actively involved.

On the exhale the movement of the:

Diaphragm- passively rises to its resting state.

Organs- rise and push the diaphragm up, all returning to their place of origin.

Lungs- passively returns to an unstretched state (elastic recoil); expel carbon dioxide with assistance from the push from the organs rising and ribs lowering.

Ribs- return downward (elastic recoil).

Spine- Lengthens within its natural curves. (Again, do not force this movement.)4

Arms- Continue their ride, as they are located on top of the descending ribs.

** Accessory muscles may be needed during labored breathing; COPD, asthma attack, forced breathing, etc.

Now that Becky has more information as part of her physiological self, she is able to include a clearer picture of her breath and body map. Becky came to my office one day and said, “Breathing stops my freak outs!” She went on to tell me how she was walking from one class to another with a friend, discussing their “to-do’s” for the weekend. She was talking and walking, and the more she talked, the more she became overwhelmed. Then she remembered her new skill of body mapping and paying attention to herself and her environment. Becky gave her breath a moment of attention by listening physically, remembering what happens during the order of breathing, without forcing her breath. She noticed that talking about the stress was stopping her natural increase of air intake necessary as she walked. With her new way of thinking, Becky found it easier to take the next inhale. This altered her usual reaction of becoming increasingly overwhelmed, and she was able to avoid her typical “freak-out”. Instead, her breathing changed and continued as she walked and the stress became a conversation that established a plan of action. She was involved in the solution instead of being held down by the workload.

Myth #4: The inhale and exhale should be the same length.

Our smart minds want to make inhalation and exhalation equal. This is not necessary or correct during normal activities or rest. Breath is like a wave; sometimes it is long, short, deep, shallow, quick or interrupted. Inhalation can be one length and exhalation another. There is also a slight pause between inspiration, expiration and the following inspiration. This hiatus varies with each situation, sometimes it can be miniscule or quite long, but it is a part of the wave like quality of breathing and is important to include in your map of breathing²·³.

The variances of breath are there to meet the needs of the greater picture: you living in a world that is ever-changing. Here are a few examples: When you meditate your breath will slow naturally because you are not using as much oxygen. When you exercise your breathing becomes quicker and deeper because your muscles release more carbon dioxide; your body needs to get rid of it and bring in more oxygen. If you are reclining in bed your breath will slow down and become shallow; as your body rests it needs less oxygen to function.

Everything we do creates its own unique breathing pattern that does not need us interfering with it. Yet, you may find that when you notice your breath, there is a fixed desire to take over. Instead, you can practice observing your breath, without meddling with the outcome.

Try this:

First, recognize how quick your mind is ready to take over and guide.

……………………………

……………………………

……………………………

……………………………

Okay, your mind can be bossy. Now that you have noticed this try a different approach:

“Flash in”, wherever you are in your breath and then go back to whatever you were originally doing. As quick as a camera flash, you can briefly feel your breath, notice where you are inhaling or exhaling. Simply feel that and then stop paying attention. Notice the sounds outside or the chair you are sitting in. By briefly observing you are able to peek at what is happening- movement, expansion, exchange, rest, and recoil. You are able to feel your body at its natural state within the ebb and flow. There is a great deal to observe and feel. With practice you will be able to listen for longer, and enjoy what you feel without changing the already occurring natural flow. There are many benefits to observing breath in its organic state. It helps create the conditions of listening to your body, a beginning step of Alexander Technique and other mindfulness practices such as meditation. You develop inner trust, which can be helpful during times of stress, being rushed or feeling unable to rest. This practice can become an ongoing lifetime investigation. You can use observing breath as a sensation of inner newness; each breath is new and unique. Let it be that, just as the oxygen is that comes into your body.

We think of breathing as an in-and-out process that moves air. It is so much more than that. Our respiratory system works directly with the circulatory system, which flows blood and delivers nutrients throughout all the cells in the entire body. Together the two systems keep our body energized, expel waste, and keep us in homeostasis. What a relief we don’t have to think about that while also answering emails!

Becky found a way to pay attention to her body by listening and knowing that breathing was one thing she didn’t need to make happen. She started to separate her own human body from her to-do list and expectations. As our Alexander Technique lessons continued, we applied flashing in and listening as a base and examined her chosen response to other situations; ballet warm-up at the barre, typing at her computer, leading a group and giving a presentation.

Breath underlies movement in the body, so if your body is held in some way during breathing, this holding is carried on to other activities. Even when doing something that seems unimportant: chopping vegetables, walking or petting a dog- holding within yourself might still be present. In Alexander Technique, understanding and awareness of breath can be the first step toward speaking, singing, as well as other seemingly un-physical activities, like sitting in a chair.

*Although common and effective, hands-on guidance is not necessary or required to study Alexander Technique. Hands-on guidance is always used in accordance to student’s comfort level and request.

Edited by Jeffrey Biar and Laurel Perkins

_____________________________________________________________________________

Reference List

- Alexander F.M. The Alexander Technique The Renowned System of Mind-Body

Coordination. 3rd ed. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing Group, 1995.2

2. Jenkins G., Kemnitz C., Tortora G. The Respiratory System. In: Roesch B, ed.

Anatomy and Physiology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007: 834-857.

3. Norris C. Nursing Assessment Respiratory System. In: Green K, Horn J, ed.

Medical-Surgical Nursing Assessment and Management of Clinical Problems. 8th ed. St.

Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2011: 497-518.

4. Conable B., Conable W. How to Learn the Alexander Technique A Manual for Students. 3rd Portland, OR: Andover Press; 1995.

5. Ibrahiam A. Muscles Involved in Respiration. Slideplayer.

http://slideplayer.com/slide/9683031/. Published Unknown. Accessed February 15, 2018.

6. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/diaphragm-anatomy. Published July 20, 1998. Updated August 26, 2014. Accessed February 15, 2018.

7. Chapter2: Abdomen-part 2 Diaphragm. Health Appointments. https://healtheappointments.com/chapter-2-abdomen-part-2-essays/8/. Publication unknown. Accessed February 15, 2018.

8. Premkumar K. Figure 3.21.brainKart. http://www.brainkart.com/article/The-Thorax_20921/. Published July 31, 2017. Accessed February 15, 2018.

5

5